Eyes up! The young birdwatching community is taking flight

The thrill of nature’s call is revitalising a hobby once reserved for old men in anoraks. Aaron Sterling shares the joy of birding

The thrill of nature’s call is revitalising a hobby once reserved for old men in anoraks. Aaron Sterling shares the joy of birding

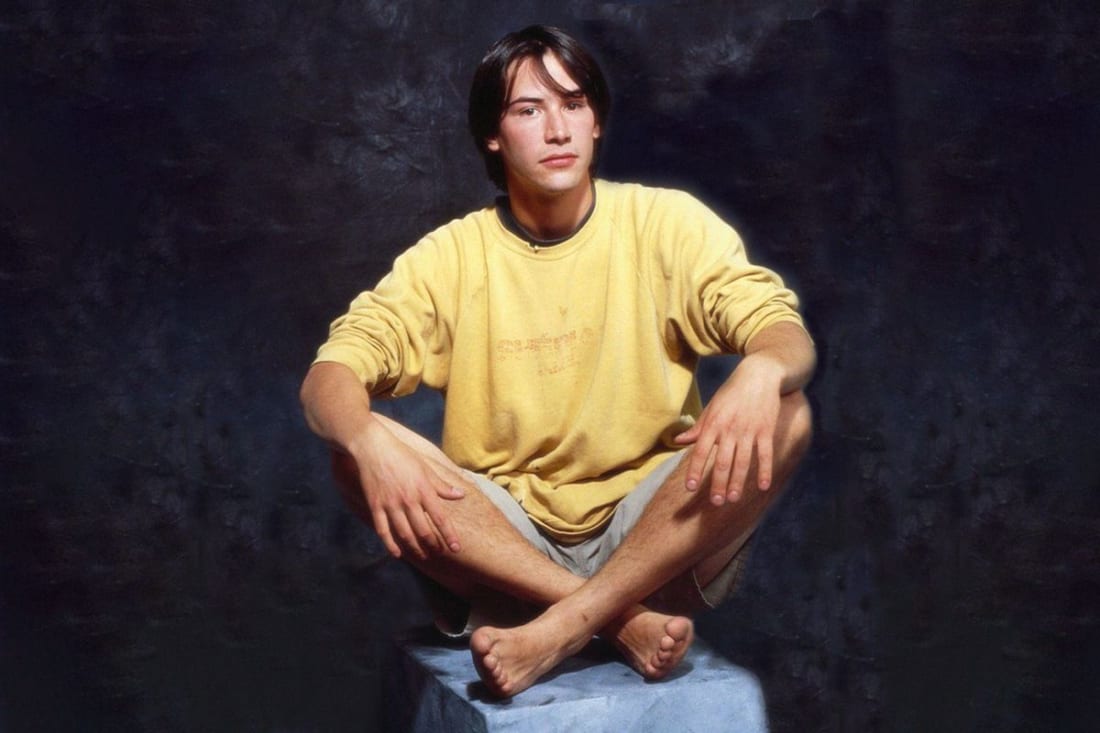

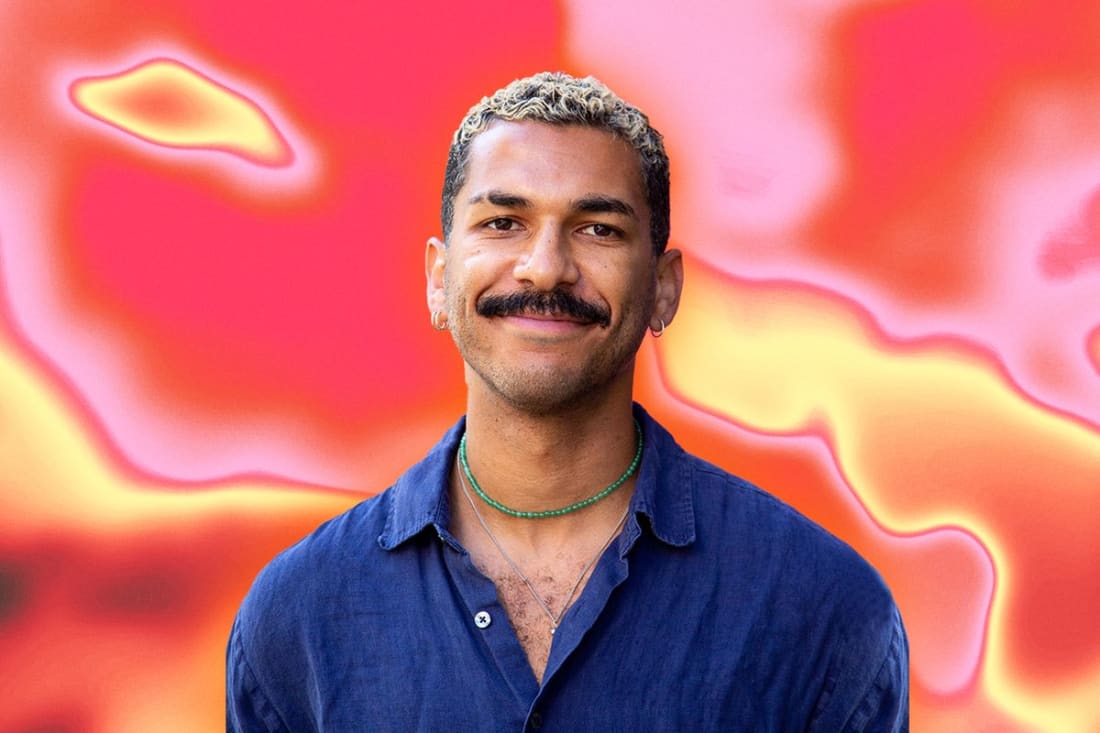

Aaron Sterling is laughing about how his once particularly clandestine passion is now en vogue – a hobby du jour. “When I was in my early 20s, it was a lot more hidden,” he tells me over Zoom, dressed in an all-black tracksuit and working a big smile. “So I wasn't really shouting from the rooftops: ‘I watch birds’. That’s changing now!”

Sterling, now in his 30s, is witnessing his beloved citizen science herald a new era, with an online, global community of diverse young people discovering birdwatching. Young people are boosting a collective interest in what 10 years ago – maybe even five – was generally considered the reserve of older, white, middle classers who could pick a Nightingale out from their battered old birding book with the same ease as they could spot Bill Oddie in a crowd. The ‘birdwatching’ hashtag has 167 million views and counting on TikTok, where young, new birdwatchers contrast and compare local birds from their regions and share tips.

Sterling has been active in this online community, and also works as a wildlife photographer and birdwatching advocate. He first became interested in birding after receiving wildlife books from his mum aged 10, and finding himself drawn to the winged variety, and begging her for binoculars. His initial tallies recorded what you might expect from someone situated in the inner city of Birmingham: “It was like: ‘Seagull times six. Pigeon, 200,’" he says with a laugh.

It’s simple enough to suggest that after a protracted period of being inside during lockdown, people’s interest in the outside has boomed. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) noted a 70% increase in website views over the first lockdown, with more than 50% of those on pages looking at bird identification.

Sterling encourages people to get out there, and really look around. In episode two of Woo's Nature Calling, he introduced hosts Mary Steven and Niko B to the joys of bird-watching, for the first time. He does quick run-down for beginners like me: the Robin (friendly) Sparrowhawk (not friendly) Mockingjay (known for mocking other birds' songs), Bullfinch (“you have to see the colours up close”).

I ask him what his favourite bird is, and he screws his face in mock anguish: “Can I pick two?”. Eventually, he settles on the Kingfisher, because of its rarity and dazzlingly tropical, fluorescent orange and blue feathers, and then the Short-eared Owl, because of its mystery and expert predatory ability (“a crazy bird!”).

During our chat, I take this advice and keep one eye out of my window in Brixton for a while. I seek some joy from the often-overlooked blurs darting around the south London sky. Half an hour later, I find myself transfixed – small, brightly pigmented lime green birds settle on a tree outside my door, perching over a car. Sterling tells me these are Parakeets, which is news to me. He makes the point that they’ve probably visited every day, I just haven’t thought to really look at them. This, for Sterling and other birders, is a major part of it – it’s about finding new ways of seeing after a period of stasis.

A typical birding afternoon sees Sterling suited up in camouflage (often with a tracksuit like the one he wears now underneath) and might see him out for six to eight hours walking around RSPB nature reserves. He’s usually armed with a pop up chair, a 600mm lens Canon, and a Kit Kat Chunky if it’s a particularly long day. He will stay completely silent to listen out for birdsong, his favourite being the Blackbird. This is most typically heard during the breeding season, from March through to July – it’s one of the UK’s most prolific, and one you’ve probably heard twinkling above you in the spring.

It can be a struggle, he admits, not to reach for the airpods. But there’s nice advantages to being open to birdsong to keep in mind on your next jaunt outside: in 2019, scientists at the University of Surrey studied the “restorative benefits of birdsong”, testing whether it really does improve our mood. They discovered that, of all the natural sounds, bird songs and calls were those most often cited as helping people recover from stress, and refocus their attention. Being in nature, full stop, is good for us too of course – in the 1980s, researchers at the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo first published their research into the health benefits of shinrin-yoku (which you may know as ‘forest bathing’), which showed that nature calms the stress response in our central nervous system, and can contribute to blood pressure reduction, improvement of autonomic and immune functions, as well as of alleviating depression. In 2019 too, the RSPB released a single of birdsong for International Dawn Chorus Day (May 5, stick it in your diary) that actually cracked the UK’s music charts – it featured once common British bird species like the Starling, Swift, and endangered Turtle dove and Grey partridge, to draw attention to British birdlife’s extinction worries.

Anecdotally, Sterling feels the benefits, and wants you to feel it too. He’s evangelical about how searching for an elusive Kingfisher can be what he calls ‘a cheat code’ to calm. “If you do actually take the time to get out in nature, the benefits are crazy,” he says. “Like I can be, ‘Ah, can't get through this week’. And the weekend, I'll make sure I get out, phone off, slow down, and de stress. We live these really fast-paced lifestyles, don’t we?”

The act of something as small as birdwatching as a person of colour, especially a young Black man, can feel radical too. It’s an act of taking up spaces that have been overwhelmingly white. “I've had people see me and be like, ‘Are you in the right place?’ There's the whole (prejudice) thing of being quite big, strong, and aggressive. But it's like, ‘Nah, man. We just sit in a hide and watch birds. Happy days’,” he says.

In 2020, a white woman, Amy Cooper, called the police on a Black male birdwatcher. The incident made international news, and it sparked debate about just who is able to enjoy nature in peace. How can we expand the accessibility of green space for some communities who are made to feel like outsiders and aggressors? Groups like Flock Together, a birdwatching collective for people of colour, Facebook meet-up groups like POC in Nature, and British Birdwatchers are testament to a mission to reclaim green spaces for people of colour and the most marginalised.

Sterling takes Woo, armed with binoculars and a positive, skyward-facing attitude, into the hills for a hike. We’re on the look-out for a Red Kite, thrilled at the excitement of a prospective Heron spot and a shared mission for a glimpse at Starlings.

Sterling hopes to get a diverse range of people as excited as he is about rediscovering birds. His infectious energy and enthusiasm is palpable. I ask him how successful he’s been in recruiting friends. “When I'm pushing it to people, I just feel like I’m sharing a secret, and when they come out, they're like, ‘Yeah, this is sick’.” The camo and tracksuit uniform he dons is a sartorial, aesthetic plus. “They love the drip. They love the swag,” he says with a smile.

Birding and its impact on mental health may have long term effects, with new research suggesting a positive link between the hobby and the care of dementia patients, concentration, and even eyesight, as distance viewing (looking at horizons far away) is good work for our eyes. As global warming sees the concerning change of migration patterns, birdwatchers are seeing the impact of climate change first hand in the future – a dynamic and crucial way to get people engaged with the climate emergency, and one that could inspire more collective action and responsibility for the planet should we be concerned for our feathered friends.

Sterling continues to be inspired by the burgeoning birdwatching communities both URL and IRL, and as a simple, beautiful hope for an optimistic future world. Before we part ways on our hike, he articulates a simple dream for the future: “I would love for a day for me to go to a nature reserve and there's all sorts of people there.”