Why Gen Z is worshipping at the altar of neopaganism

From traditional celebrations to transcending at the club, young people are embracing pre-Christian forms of spirituality

From traditional celebrations to transcending at the club, young people are embracing pre-Christian forms of spirituality

Maybe it’s due to the seasons changing and being able to take a deep breath of honeysuckle every time I step outdoors, and feeling my lungs fill with lots of tiny, fragrant particles of the universe. Perhaps it’s a product of having perpetually frayed-at-the-edges mental health, where my mind tends to rub up against the jagged reality of my own mortality more than it really should. But recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about God.

Regardless of my reasons - which seem especially valid when we look at the Hellfire that is the news cycle - everyone I know seems more than a little suspicious when I reveal my quasi-religious leanings. Their response is, I know, likely a result of being openly ~ sex positive ~ and queerer than Joseph’s Technicolour DreamCoat, qualities which have traditionally alienated me from organised religion. And no matter how politely I rationalise my theory that the phrase “the universe works in mysterious ways” is extremely Holy Spirit-coded, every time I mention God to friends I’m always regarded as if I’ve lost any semblance of reality and have started trying to convert people at the pub.

Faith is a highly personal thing and something which no-one should be able to take from you. That said, having to ferociously defend what is little more than a latent religious inkling just seemed like far too much hassle - the need to bow to peer pressure was apparent. So, I set out on a quest: if people are so vehemently against my neo-Catholic leanings, was there another form of spirituality I could tap into and experiment with on my terms, without, as white people in search of enlightenment have been wont to do, appropriating someone else’s cultural beliefs?

The answer came from a surprising place - right around my neck. See, around the height of the Christiancore renaissance last year (which I have written about elsewhere) I started to wear the Celtic cross. Growing up in 2000s Scotland where sectarianism was still very much on people’s minds and us kids had it drilled into us not to wear any outward reference to our religious affiliation, it felt subversive to wear such a blatant symbol of faith - I like to imagine it’s how Addison Rae felt when she wore her internet-breaking Praying bikini.

But even as the Christianity trend faded, I kept on wearing my cross pretty much every day. This wasn’t necessarily a demonstration of faith, but a nod to my Scottish upbringing and the Celts who - like many other groups of people across the world - found ways to interweave their own cultures with newly adopted religious teachings.

In fact, it’s Celts - polytheistic, who worshipped divine feminine energy and, it’s speculated, certain trees and facets of nature - who I’m turning to during this particular spiritual crisis. Knowing that the traditions of these ancient groups aren’t really around anymore, I’m toying with certain elements of paganism. No, not devil-worshipping or orgies (that would actually be more on-brand for me) but rather picking-and-choosing folkloric rites that feel like a good fit for what I’m trying to get out of religion - a sense of connectedness, a way of relating to nature and a groundedness in ritual. And, as it turns out, I’m really not the only one.

The resurgence of paganism and folkloric ritual in the UK

This year I started noticing people posting photos from their Beltane - that’s the Gaelic, Pagan festival taking place on 1 May - celebrations online which, in itself, is something to talk about. What I once perceived as a fringe celebration for hippies was now something that my acquaintances and even friends were partaking in. What gives?

Well, a rise in the popularity of paganism apparently - and, no, I'm not just talking about the Aries x Umbro collab emblazoned with “Pagan” logos or Simone Rocha’s AW23 ode to Ireland’s pagan Lughnasadh harvest festival. The last England and Wales census showed that self-identified pagans have risen from 57,000 to 74,000 over the past decade - and that doesn’t include Scotland, where there’s an additional estimated 10,000 pagans and wiccans.

For the uninitiated, the term “paganism” refers to a range of traditions including Druidry, Wicca, Goddess spirituality, shamanism and animism. It’s a word that was first used by early Christians in the fourth century in order to describe non-Abrahmic religions, particularly those which were polytheistic. Because pagan is actually an umbrella descriptor, there’s no one way to practise paganism but, generally, these forms of spirituality might encourage things like nature worship or following the Wheel of the Year: a calendar of festivals which celebrate the change of the seasons.

But beyond those who root their identity in pagan religions and cultures, there are others - like myself - who are interested in exploring their symbolism and teachings as part of a wider spiritual practice.

This is the case for 28-year-old Ellen*, who first began experimenting with witchcraft and paganism a decade ago at university but only started taking it more seriously during lockdown, when a reconnection with nature led to a recontextualisation of her spiritual beliefs. “Paganism became a more serious thing for me during lockdown as there was more time for me to practise,” she says. “I also got really into gardening, it gave me more purpose and paganism helps me with the rhythm of the year and the changes of the season.”

Now, three years on from the first lockdown, she’s still in touch with her newfound faith. While she’s not specifically interested in the Gaelic and Celtic traditions like myself, she recently travelled to Hastings from London to attend the Jack in the Green festival - an annual ceremony that coincides with May Day. While folkloric rather than explicitly historically pagan, the festival ties into elements of the Pagan calendar and plays with the symbolism of the Green Man, a Mediaeval sign of rebirth depicted via a man peering through dense foliage.

For Ellen, and many other people in attendance, the appeal of the celebration is about feeling at peace with the passage of time. “The ritualistic stuff around paganism and folklore feeds into my happiness,” she tells woo. “For Jack in the Green, you slay Jack who represents winter and by doing that you welcome spring. But it’s not sad because he’s going to be back in October for Samhain, it’s a cyclical thing.”

Someone else who has witnessed the festival up close is Dominic Markes, a photographer whose ongoing project 'We Come One' explores the “collective effervescence” within England’s folkloric events. While he was fascinated with the spectacle of the gathering - specifically noting revellers dresses as mushrooms and animals and adding that “every street was lined with ivy, flowers and bunting, and everyone wore foliage and had their faces painted green” - he suggests that many of the people present, unlike Ellen, were not attracted to the event due to its pagan leanings.

After asking a sample of people present about why, exactly, they’d showed up, Dominic discovered that the reason wasn’t necessarily religious or spiritual - it was simply a chance to come together: “Some people were aware of the festival’s pagan roots but they were in the minority and if they did mention it, they often simplified it to ‘I'm here to carry on the tradition,’” he explains. “Instead, the gathering provides a chance for neighbours, strangers, friends and family to take over a public space in a way that is different from the day-to-day. The festival provides ample opportunities for those present to experience joy, wonder and intrigue together. It seems like these shared experiences - often with like minded people - solidify one’s individual and collective identity and ultimately contribute to them feeling part of a community.”

Satanic rhythms: neo-paganism and the dancefloor

Listening to Dominic’s observations from Jack in the Green, I couldn’t help but notice something. The desire to come together and escape the everyday sounds a Hell of a lot like the kind of thing I say when I’m trying to justify why I went on a two-day bender at a queer squat rave when I have a stack of writing deadlines to attend to. What - if anything - does this turn to the pagan, folkloric and pre-Christian have to do with a post-lockdown club culture where whiplash-inducing bpms are king and a new generation facing economic and political uncertainty is searching for meaning beyond the career ladder via the dance floor?

To investigate, I reached out to Rossa Doherty, a Dublin-based DJ and producer who spins harder genres like breakbeat, techno and trance and goes by the very apt artist name of PAGAN. Quickly, however, I realised that Rossa was not the world’s biggest authority on pre-Christian religions. “I know very very little about paganism, I literally got my artist name on randomwordgenerator.com and I picked it because I thought it sounded cool and I found the imagery associated really visually interesting,” he admits pretty much straight away.

He does, on the other hand, note that the club scene has been given a bit of a The Fast and the Furious-style treatment over the past few years. “Harder dance music has become heavily popularised and it seems to be the entry point for a lot of younger ravers,” he explains. This, he adds, makes raving right now a bit of a mad one. “This style of music seems to evoke much more intense, energetic dancing than other genres,” he adds, noting that this looks pretty cool on social media, which is likely why it’s spread so quickly. There’s also the fact that dancing really does help us feel like part of something bigger, something which the Covid generation may have missed out on when locked away in their rooms for two years; “Dancing as a group of people can create a real sense of connection.”

Traditionally, queer theorists have looked to the rave as a kind of a speculative, forward-facing utopia, a space where we can collapse the hierarchies of the wider heteronormative world, bend our perception through drugs and side-step the rigours and restraints which capitalism places on our body and our time by moving wildly, wasting hours and imbibing substances that will make us far too hungover to productively contribute to society.

But in her recent book on the matter, Raving, theory doyenne McKenzie Wark complicates this take - pointing towards both the profit-driven industry which nightlife works within, the very fleeting joys it brings and the fact that our lives seem more uncertain than ever; “Today's raves are hardly a situation that prefigures utopia. They cannot prefigure futures when there may not be any. The constructed situation of the rave may be all some of us have - even if the revolution comes.”

And that’s all a very long way of me saying this: what if raving today has given up on gesturing towards a more progressive future and is instead drawing from the past to create a sense of community? Nowadays, we tend to accept that raving probably won’t change what lies ahead or create long-lasting political solidarity (join a union for that, babe). But what happens when you add spirituality and pagan symbols into the mix? Beyond acknowledging that raves are a passed-down, diluted version of the kinds of ancient festivals which neo-pagans are trying to revive, could the addition of religion help elevate the nightlife experience to loftier heights?

Of course, there’s long been some link between raving and paganism, even if it’s tacit and harder to detect. After all, summer solstice parties are dime a dozen and Glastobury, home to the eponymous festival, is thought to have been a major site of pre-Christian belief as well as a current day hotspot for Wiccans. But how do the new generation integrate spirituality into the sesh?

If you live in London, you don’t need to look too far to find an example of this in action thanks to GR1N, an esoteric, swampy underground rave which has brought the hardcore, uberpop stylings of Umru, Swanmeat, Jennifer Walton, Hannah Diamond and Babii to venues like Corsica Studios and Colour Factory. Rather than a traditional dance party, the event plays with notions of the occult, styling itself a techno-spiritual sect via ritualistic performances in the club and event-goers cosplaying as cult members. If anything will give your fair weather Fabric fan a dose of satanic panic, it’s this.

The organisers of the event describe this melding of audience participation, live art and dance as “rave as LARP” and note that the club has always had religious leanings. “The rave space is like a contemporary church, with everyone surrendering power to this amorphous entity with the music, and we try to create architecture, installations, and performances that mean people can really lose themselves to a fictional world,” they explain.

For the collective, touching on the occult is a way to channel traditions which transcend the club and have a deeply rooted history which contrasts to the immediacy of the dancefloor. “There’s a sense too with neopagan aesthetics that you’re accessing something quite powerful, sigils and these kinds of rituals seem to have a lot more weight to them,” they explain.

Ultimately, leveraging pre-Christian symbols in these kind of cultural spaces is about digging into the past for something which can help tether you to the future. “We would say people are engaging with esoteric or neo-pagan ideas as a kind of escapism, but not in the sense of ignoring or deflecting from everyday problems and struggles, but as a way to produce a new reality. The present and near future looks pretty bleak, so people are trying to produce their own narratives.”

Pagan dreams, everyday nightmares

If mulling over the state of my eternal soul or speaking to budding folklorists and techno pagans has taught me anything, it’s that we’re all in a bit of existential turmoil. Perhaps it’s always been like this - people did think that the world was going to go into cyber meltdown at the millennium, and people in the ‘60s through to the ‘80s were literally living in fear of nuclear war - but it does feel a lot like the world around us is crumbling under the weight of authoritarianism, environmental destruction and that creeping feeling that the human race is doomed to keep fighting and hurting one another for no reason, until we all eventually wipe ourselves out.

That’s all to say that we’re all a little in need of guidance and, whether it’s on the dancefloor, at the chapel or during a Celtic ritual, we need to hold our moments of spiritual freedom close. Maybe I’ll dive further into Gaelic pagan rituals, or maybe I’ll remain content with my own, very loose interpretation of Catholic faith. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter - all paths lead to God (or Satan) after all.

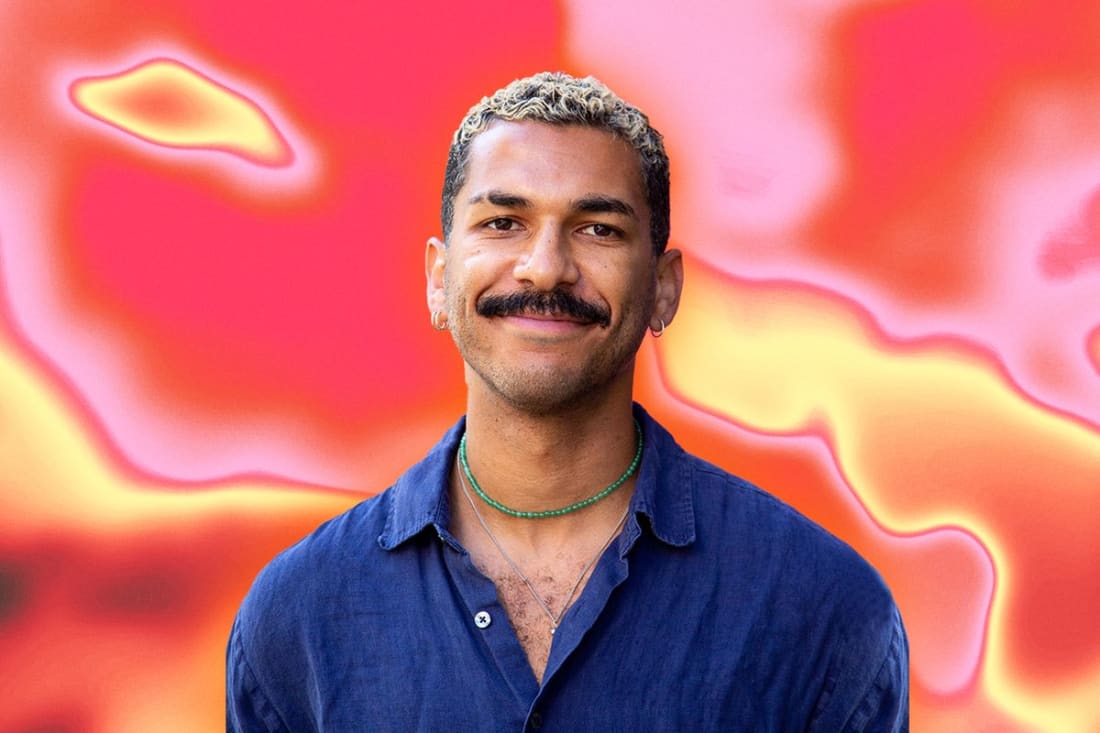

Cover image by Tom Kelly.

In-article images by Dominic Markes.

*Name has been changed