Delve into Ajamu X's erotic takes on traditional Black masculinity

Unfiltered and unapologetic: Ajamu X is the photographer responsible for lensing a generation of Black queer sexuality

Unfiltered and unapologetic: Ajamu X is the photographer responsible for lensing a generation of Black queer sexuality

“I come from a town where they had very fixed ideas around masculinity and gender – as a kid who was into post-punk, goth and mascara - I didn't quite fit with this idea of 'Black.’” photographer Ajamu X never quite felt like he belonged, growing up Black and queer in a small town in Huddersfield in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

A creative child through and through, it wasn’t long until he was drawn to the arts as an outlet to explore and share his gender and sexual identity. After launching an alternative magazine, BLAC, in 1984, he picked up the camera and hasn’t put it down since.

“I needed images for an article that I was working on,” Ajamu recalls. “I got a camera and started to take images of people around the town. But I also started to photograph Black men that I was attracted to – the camera then became a way for me to start trying to ask these questions of myself.”

It is this endeavour to understand his own sexuality, as well the changing landscapes of the queer community and where he sits within it, that have fostered Ajamu’s now 30-year-long career lensing queer Black Britain. “Photography has allowed me to document the world through my own idiosyncratic lens of a Black queer kid from the North. So part of the work is certainly my worldview,” he tells woo. Influenced by his own experiences of estrangement and difference, Ajamu has spent his career investigating what it’s like to be a first generation Black person in the UK who is queer and out. It is this question that echoes through his latest exhibition at Autograph Gallery: Ajamu: The Patron Saint of Darkrooms.

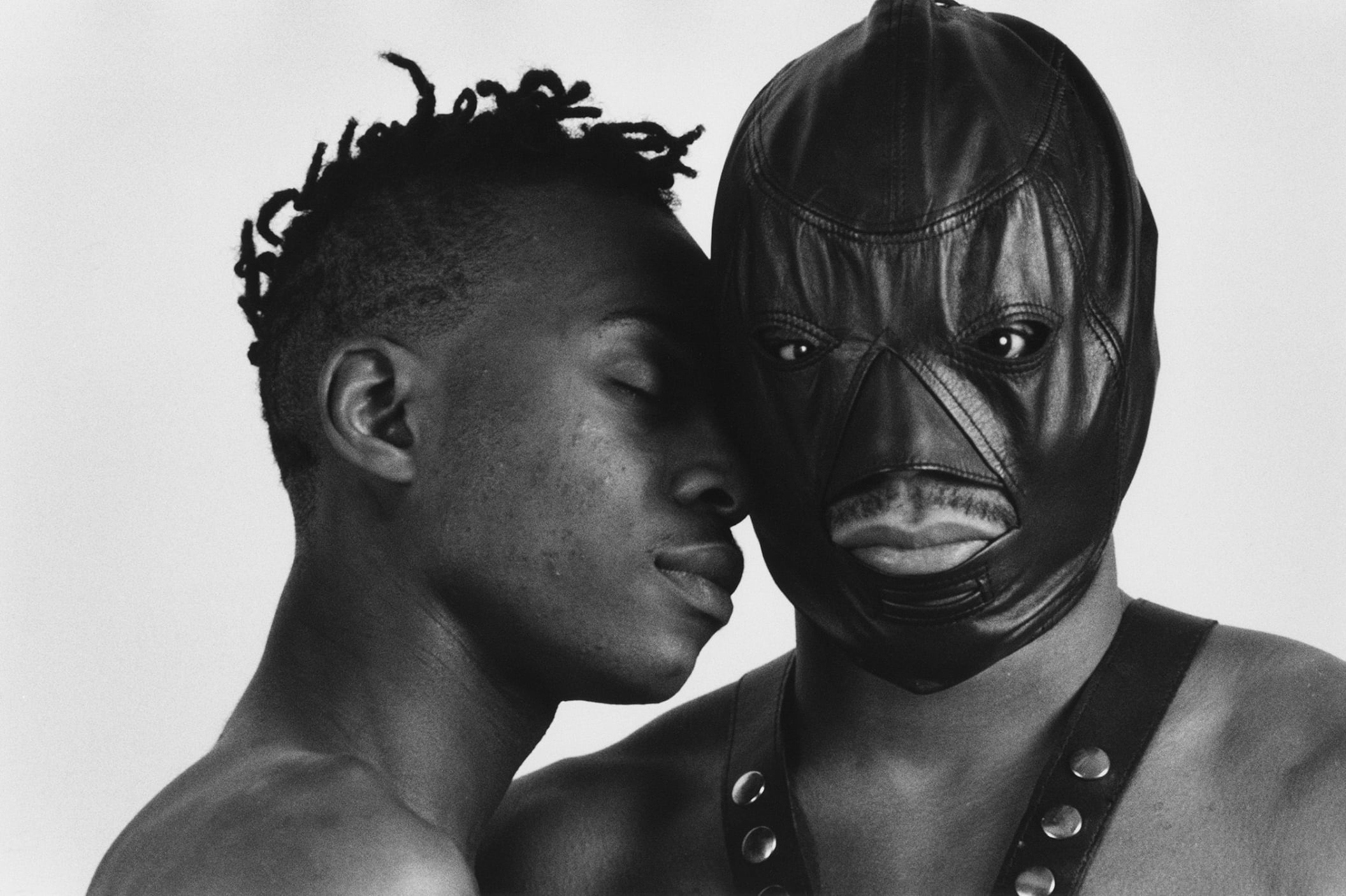

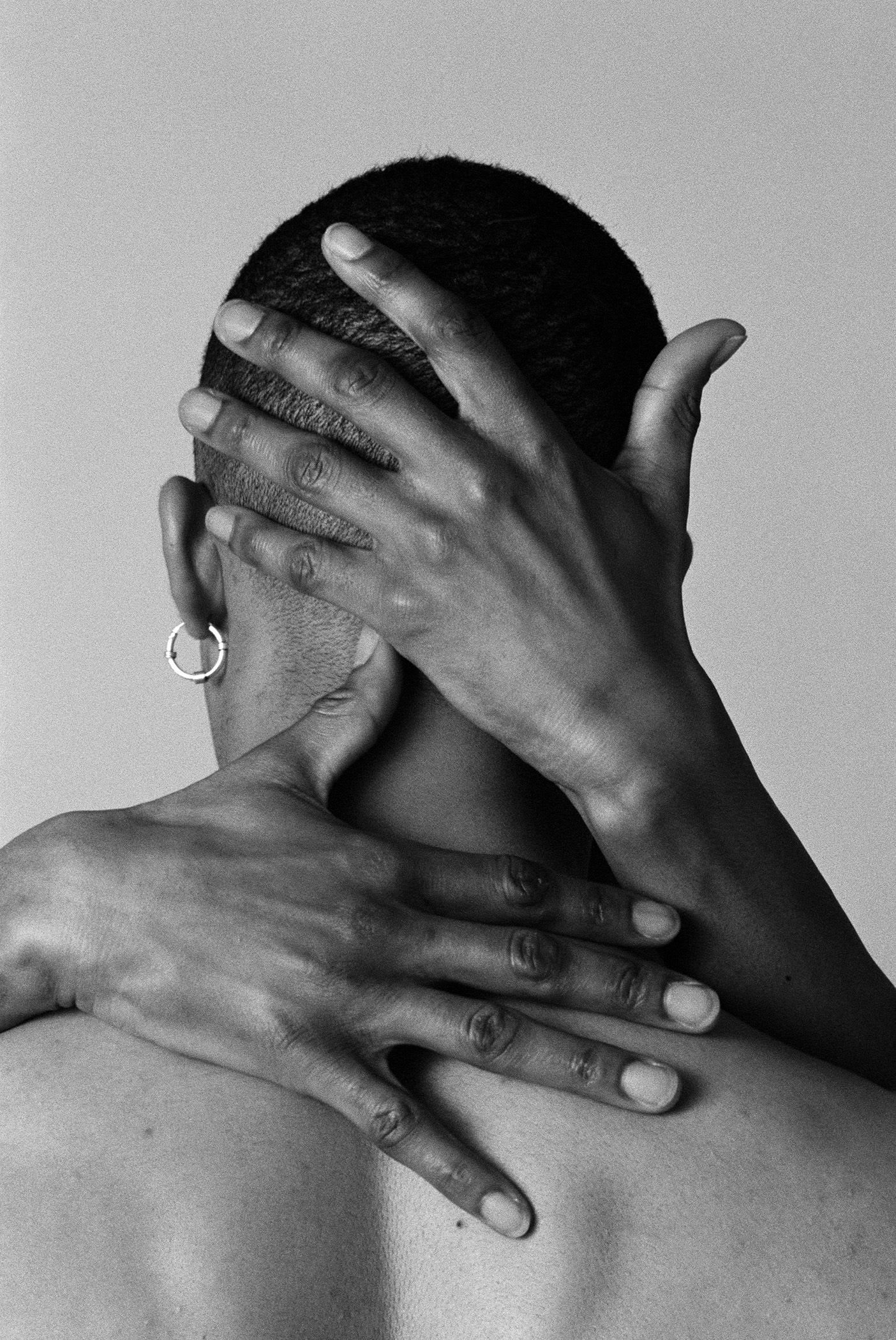

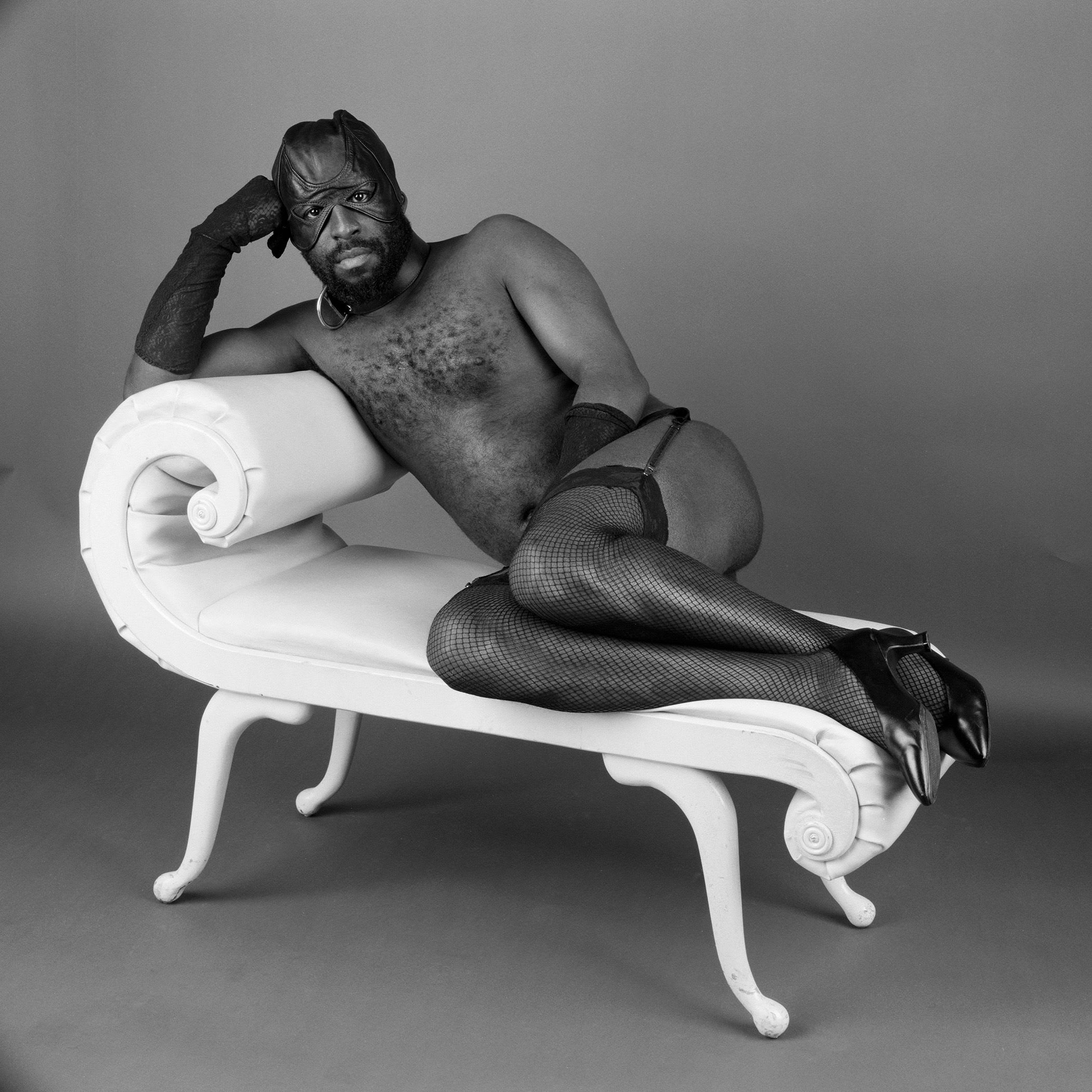

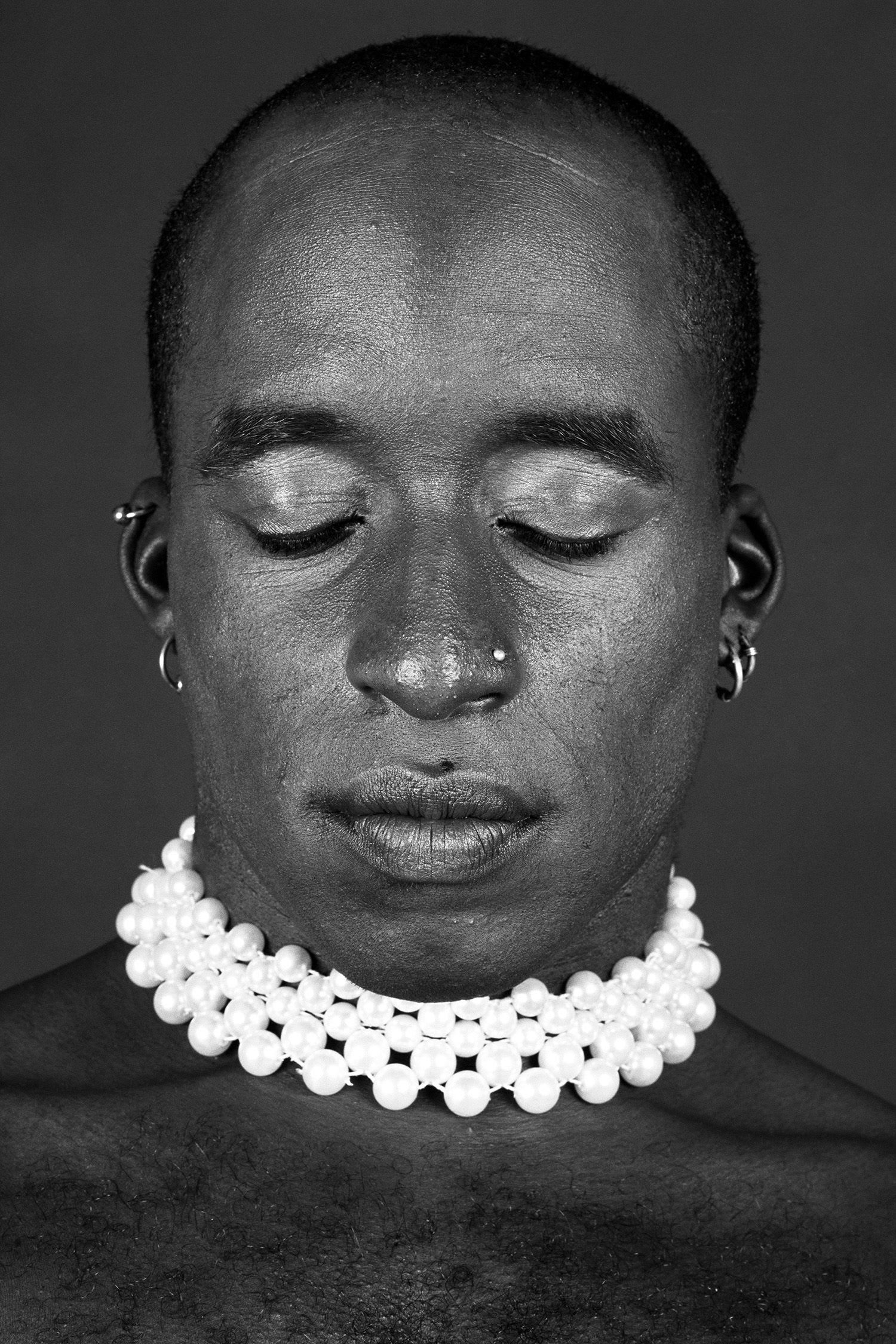

Be it tender and intimate images of lovers, exploratory self-portraits or his more recent work capturing joyful portraits of Black trans men, The Patron Saint of Darkrooms celebrates the erotic, challenges normative expectations of masculinity – particularly those placed on Black men – and tenderly investigates the politics of pleasure. To celebrate the launch of his exhibition, woo caught up with the prolific photographer to reflect on his creative vision for the project, the changing landscapes of public art, and what queer Britain looks like today.

Congratulations on the opening of your exhibition! The Patron Saint of Darkrooms is a collection of your work across your career, why are you showcasing them now?

Well, the exhibition is not a retrospective. What it does is it gives people a very broad overview of some of the issues I've long been working with. [The exhibition] also includes new work as well, like platinum prints of Black trans men who are born and raised in the UK.

Over the last few years my work has been taken up by larger institutions because things have shifted socially and culturally; the thing that people forget about the early ‘90s is that Section 28 (a Thatcher-era piece of legislation that prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” by local authorities) still had this overarching influence over what kinds of work would and wouldn’t be shown. My work is entering collections now, partly because we're seeing younger curators enter the space who focus on diversity and inclusion. So I actually haven't really shifted – I’ve been able to drill down further into these topics as cultural ideas shift and change.

You mentioned you started out photographing men that you were attracted to. Did this help you explore your own sexuality?

Yes. Through my self-portraits I’m allowed to question my own sexuality; the things that turn me on. I think photography does that very well.

What importance do you place on showing joy and pleasure in your work?

A lot of social justice movements historically have ignored the erotic and pleasure. You could argue that people join groups to create some kind of social change – that's a fact – but we're also joining groups to get close to people. The reason why I go to joy and pleasure is because I have to ask; how else am I in the world? I'm not only in the world through a public lens; I'm also in the world as a friend, a family member, a lover.

The exhibition creates an unapologetic space to celebrate Black sexuality – what do you think the work is doing for queer Black visibility?

I push back against ‘visibility’. Yes, visibility and repetition is important, but actually, this thinking locks the work within a sociological framework, and that's a problem when we engage with photography. There’s a danger that people think just because the artist is Black and queer, the work is only about representation. I'm saying, well actually, I'm also a technician and a craftsperson.

Given today's rise in anti-trans discourse and attacks on the queer community, would you say that your exhibition is coming at an essential time?

Every time [period] needs to be celebrated. But the reason I’m excited for this work is because I think that conversations around nature, nurture and the binary are now redundant. I don't think that a binary framework has any place in how we think about people’s lived and complex experiences anymore.

How do you hope to make people feel when visiting the exhibition?

I hope that people who visit are not just those part of the community because that’s too narrow. The first thing that I want people to get from it is beautiful photographs; well-crafted imagery. I do want people to come and see images that might provoke questions, and hopefully see images that they might not have seen in this particular way previously. That's all I can hope for. The key is for people to come and get a sense of my particular Black queer British experience.

Ajamu: The Patron Saint of Darkrooms will exhibit at Autograph Gallery, East London, until 2 September 2023.